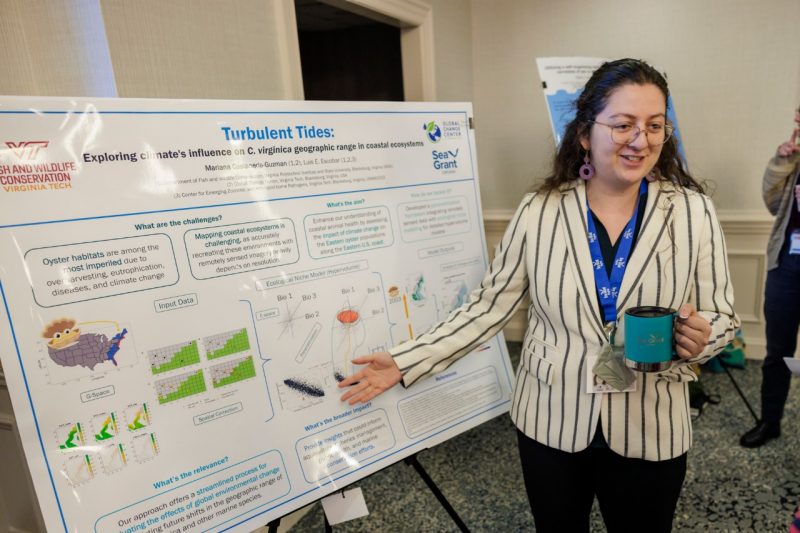

Mariana Castaneda Guzman: Demystifying methods

This piece was written in the spring of 2025 by GRAD 5144 (Communicating Science) student Kelsey Jennings as part of an assignment to interview a classmate and write a news story about their research.

Picture the dozens of attributes that made you choose your home — your city, state, even country. Maybe it was the weather, your proximity to family and access to education, its walkability and “vibe.” Likely, it is these and a multitude more that you didn’t consciously consider; they just felt right.

We spend our lives making these complex decisions based on a host of inputs, trusting our gut, our pros and cons lists, or any number of other vague approaches. But what if we could measure each of these amorphous inputs, adjusting them to find the perfect condition? Would it change how we made our decisions? Would it help us find our perfect place? Mariana Castaneda Guzman, a Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech, is asking this question. But instead of mapping humans, she is mapping species.

Born in Guatemala, Castaneda Guzman moved to the United States in high school and got her bachelor's degree in systems engineering. But challenging work visas and a looming pandemic made her shift away from engineering.

After a chance meeting with another Guatemalan scholar, Luis Escobar, a disease ecologist at Virginia Tech, Castaneda Guzman transitioned into a fisheries and wildlife program.

“He’s very much an ideas person, and I just got hooked! He had ideas and I knew how to code. It worked out really well,” Castaneda Guzman says of their partnership. While she didn’t come to her master’s program as an ecologist, she found that many ecologists seemed to lack the coding and methodological knowledge that they needed to really understand their analysis.

“People in R [programming language used in ecology] feel like, ‘Oh, I just put this here, and something happens, like magic!’” she explains. “My goal is to create a framework for people to understand how parameters affect [their] predictions.”

To achieve this, she is creating “experimental simulations with virtual species,” developing a virtual species and its habitat and programming a host of specific environmental conditions. She will then manipulate these conditions to illustrate clearly how small changes in a model can cause cascading impacts in its predictions, helping ecologists understand concepts in a controlled environment that can be applied to modeling real species.

Ultimately, Castaneda Guzman wants to have her own lab focusing on demystifying methods. They are often overlooked in ecology, where a desire to work with charismatic species often outshines the day-to-day work.

“[Methods are] somewhere in the in-between, but if we didn’t have them, we wouldn’t be able to get to this end,” she says. “When people think of conservation,” she adds, “they don’t really think about methods,” instead picturing flashy wildlife biologists or people telling you to recycle and eat organic. As a result, budding ecologists coming into fisheries and wildlife sciences programs may underestimate the amount of work it takes, not realizing that it requires substantial forethought into the research and analysis, and how much of their time will be spent behind a computer.

Despite the challenges, Castaneda Guzman says she feels like she has “finally found the path I want to be in,” highlighting her excitement over the potential implications of her work.

“What if it is used for conservation and management? That would be incredible. . . But if I want to pave the way, I have to do it myself.”