Mohammad Banasaz: Looking for accurate risk assessment, one line at a time

The following story was written in April 2021 by Nicholas Chechak in ENGL 4824: Science Writing as part of a collaboration between the English department and the Center for Communicating Science.

In 2016, Mohammad Banasaz was working as a credit specialist at the Middle East Bank in Tehran, Iran. Tasked with assessing the risk associated with lending to high-profile borrowers, he noticed something that troubled him.

“The only risk measure the bank was using,” he recalls, “wasn’t adequate.”

The bank relied on a single measure of risk to quantify financial volatility—a measure that Banasaz realized was unsatisfactory.

“I saw the location of the company [that was applying for a loan],” he explains. “I had a very long meeting with the CEO… I had all the history of the financial records of the company in my hand and I analyzed them,” Banasaz says.

But although he felt the company was a safe bet, “the risk measure was telling something else.” The bank’s means of quantifying risk weren’t lining up with his internal calculations.

“So this thought, this idea, you know, emerged in my mind,” Banasaz recounts: It was time for a new means of assessing financial risk.

“We can improve the risk measures,” he says. “The financial risk discipline is a very young discipline, and there is lots of room.”

Banasaz is now a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate studying econometrics and quantitative economics at Virginia Tech, finalizing a thesis project that represents not only the realization of his initial concept but also the culmination of a lifelong interest in economic inquiry. He has always been intrigued by how statistical data can be used to explore economic causes and effects, a notion that forms the core of his chosen field.

Quantitative economics, he explains, is a means of drawing narratives from data using mathematics and statistical models, uncovering patterns in shapes and graphs, noticing and interpreting increases and decreases.

“I see that kind of like investigating,” he says. “You are investigating data, and you are telling the story."

And now, Banasaz is perfecting a novel method of telling that story with unprecedented accuracy. Over the past one-and-a-half years, he has worked with his advisor, Aris Spanos in the Department of Economics, to construct a software package capable of channeling thousands of economic observations into quantifiable models of financial risk.

The path has not been an easy one. Banasaz, a self-confessed “econ guy” with little prior programming experience, had to learn the Python programming language before he could start coding his program, one line at a time.

“Each line of code took me like a day,” he recalls. “One day, one line of code, the other day, the other line of code.” The process proved so arduous that he recruited a peer, Brian D'Orazio, and together they attended workshops and online courses and developed their programming skills. The two graduate students and Spanos made a “team of three” who turned Banasaz’s thesis project into a fully collaborative effort.

After months of work, the project is nearing completion, its hundreds of lines ready for a rigorous evaluation. His software package stands apart because it prominently integrates assumptions.

“[I] realized that the problem of the other models to measure the risk was that the developers or the professors or the businesses that are using them don’t care about the assumptions," Banasaz says.

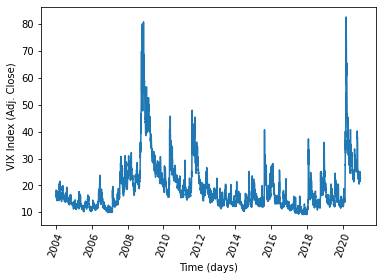

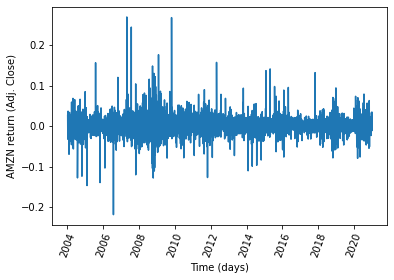

If Banasaz and his team can prove “that the assumptions—our model’s assumptions—are okay, or are fine, or are consistent in the real world,” he can verify the model’s reliability. To that end, he is working to provide real-world examples of the model at work, testing its reliability with equity prices in the New York Stock Exchange. While any such test runs the risk of revealing unforeseen flaws, Banasaz is confident.

“We have a model, a new model, a new software,” he says, “and we are sure that the model is working.”

It is not surprising that a concept so international in nature—conceived in Iran, developed in Virginia, and using the talents of a multinational team—could have global implications. Estimation of risk, Banasaz notes, is fundamental to any regulatory body and is especially crucial for those controlling financial systems.

He posits as an example the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which uses risk estimates to determine the number of liquid assets financial institutions must maintain to prevent bankruptcy. The SEC may soon be implementing models like the one Banasaz is currently developing to ensure that their estimates are correct.

The SEC, he points out, “requires banks to report their risk measures to the public, to shareholders, to everyone… and to governments,” which implement policy based on the numbers they receive.

“So if the numbers change, everything can change,” says Banasaz.

And that’s why it’s important to get it right.