Maddy Grupper: How well do you know your water?

The following story was written in April 2019 by Bianca Harleston in ENGL 4824: Science Writing as part of a collaboration between the English department and the Center for Communicating Science.

"On a scale from zero to ten, tell me the degree to which this statement describes your belief about drinking water in your home: ‘I trust my local water utility to provide drinking water to my home that is safe to drink,’" asked Maddy Grupper.

“An eight for sure,” I responded.

"Now, how familiar or unfamiliar are you with the water utility that supplies water to your home?"

“Not familiar at all,” I responded, a bit more concerned.

My responses, and those of other consumers, are what Grupper, an environmental and social science researcher, is eager to understand. As a first-year graduate student in Virginia Tech’s Department of Forest Resources & Environmental Conservation and a member of the conservation social science lab, Grupper is researching social trust in the drinking water resources of Roanoke residents.

“My research, in summary, is if trust is a gauge or a needle, will it move in response to water technology improvements?” Grupper explains. “And if it does, what direction does it move, and why?”

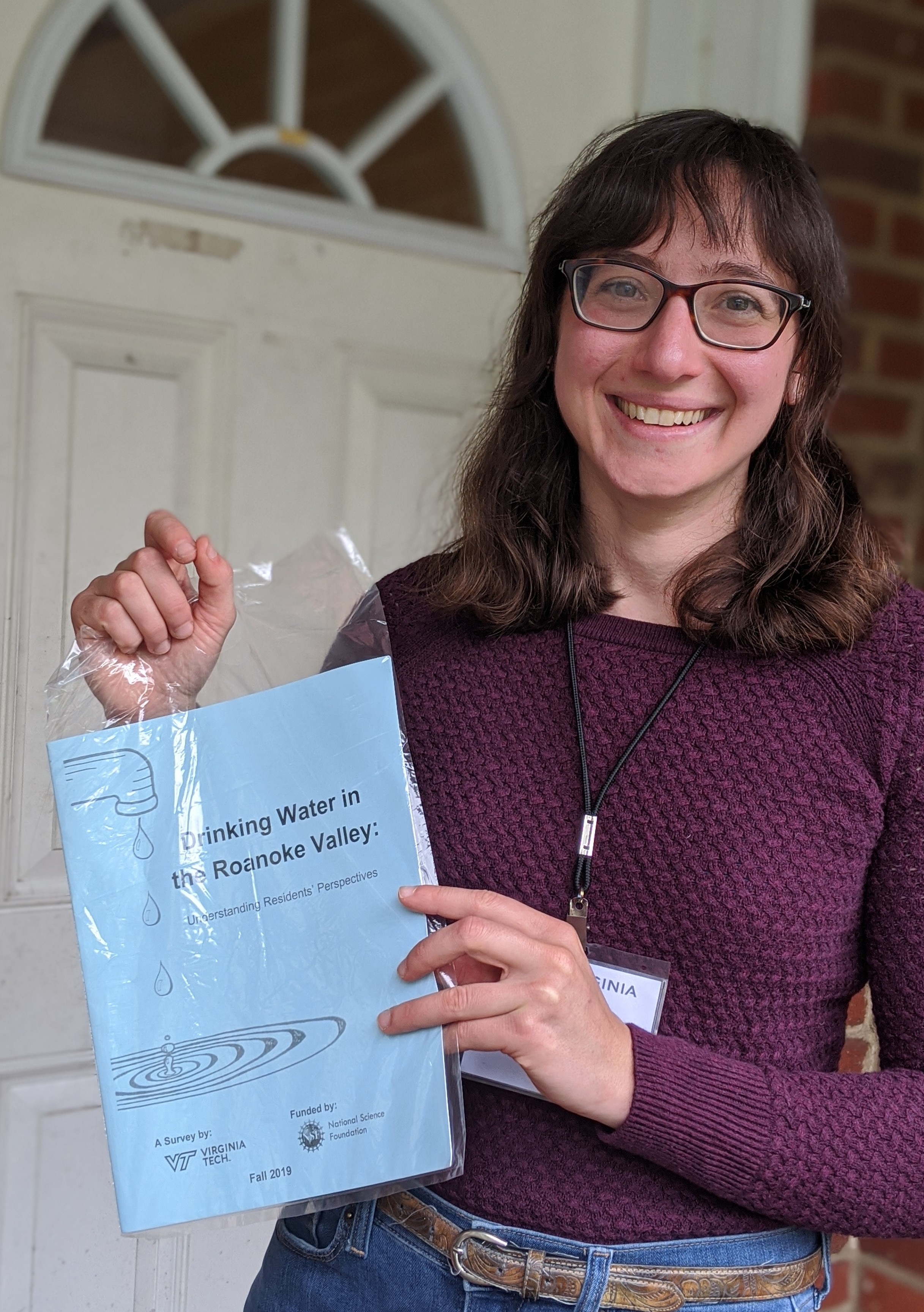

In search of answers, Grupper plans to go door-to-door asking Roanoke residents to participate in a survey that contains questions similar to those mentioned above. Each answer will bring her one step closer to discovering residents’ perspectives on the natural resources they depend on.

“Lack of trust can be detrimental to organizations that manage the water,” Grupper adds. “If there is no trust, that can hinder their ability to make legitimate management decisions that are meaningful to the residents.”

Her research has two possible conclusions: communicating about improved drinking water systems will increase people’s trust in water, or it won’t. She is pretty confident that it should. However, no matter the outcome, possible responses must be explored. If communicating the improved water technology does move the needle of trust, that will tell managers that if they want to improve public trust, they might benefit from informing the public about new technologies. If it doesn’t affect people’s trust, it tells the managers that informing the public about new technologies won’t increase trust, so they may not need to waste their resources if improving trust in that manner was their end goal.

Her research is challenging to conduct, Grupper admits, since water trust is something rarely discussed in the general public.

“I am studying how people think about a topic that they don’t usually think about,” she explains. However, she still believes that it is relevant to human livelihoods because of this fact: “Humans depend on a natural resource, and when that natural resource does poorly, so too do human systems.”

Grupper’s research is only a piece of the larger puzzle that her research team is exploring. Her 15-person team, complete with physicists, chemists, computer scientists, and ecologists, is working toward developing technology for drinking water in a Roanoke reservoir that is able to predict when changes in the water are going to occur. Her team uses a sensor at the reservoir to collect data and then a computer with a forecasting model/program to analyze the data. The model detects changes in the chemical composition of the water and then relays the information to water authorities.

“The forecasting system would tell them, for example, that ‘you are predicted to see a spike in water temperatures in the next 24 hours in your reservoirs,’” Grupper explains. This allows the water authorities to take action more quickly and effectively.

Although she is not active in the forecasting, she is proud to serve as part of the social science component of the project. She believes that her team’s interdisciplinary work is “modeling the type of science that we as a broader community need to be able to feel like is attainable” with the rising concerns of resource scarcity and demand.

While in the lab, she feels greatly privileged to be working alongside knowledgeable and driven scientists all working towards a common goal. Their work can be rather technical and advanced, which she enjoys, but she also loves to simply learn about her comrades’ research and interact with them in the lab or in their occasional rounds of kickball, she said.

Her supervisor, Dr. Michael Sorice, also plays a major role in her experience as a graduate student here at Virginia Tech. “He has been a really good mentor for me,” Grupper says.“He has a wealth of knowledge that I value and that I want to learn from.”

Sorice is an associate professor in her department, and he studies human behavior in relation to the environment, which is very similar to Grupper’s interests.

“Really significantly, his research interests are very aligned with the track that I want to go to," Grupper says. "We complement each other really well.”

Grupper feels that her research is an essential contribution to her team’s research and water research in general.

“There is a knowledge gap [between humans and their resources] and I am able to look at it in a very different way,” she comments. "We don’t often look that deeply into trust in systems that we take for granted, and I have a great opportunity to look at that.”

Overall, she believes that the best way to explore both the scientific and social aspects of natural resources is to approach them in the most interdisciplinary manner possible. Looking broadly at a topic poses its challenges and sometimes requires us to ask difficult questions, but it is what is necessary to think holistically, she says.

"Oftentimes, people look at a problem from their own unique field, but I feel like more and more there is a trend moving towards interdisciplinary science,” Grupper states. Given this trend, the best thing to do is join in on the process of bridging the gap between scientists of different disciplines and the gap between research and the general public.