Jack Stack: Discovering a new species in the 21st century

This piece was written in the fall of 2022 by GRAD 5144 (Communicating Science) student Jack Stack as part of an assignment to write a story about his research. It also helped inspire him to start a substack, where you'll find this and more of Jack's "fishy writing": https://fishhistory.substack.com.

The age of great expeditions to far-off lands to collect species new to science largely ended long before I was born. However, new species can still be found if you know where to look.

In a bygone age, naturalists journeyed around the globe by ship and by foot in a seemingly endless quest to find new animals and plants for museums and collectors. This age of science should not be romanticized; it was defined both by great deeds of towering figures in the history of science and great evils in the name of empire. The stories of the species seekers of the centuries of exploration and imperialism could fill many books with tales of heroism and greed. My work as a scientist in the 21st century stems from this history, including the good, the bad, and the ugly.

I did not discover a new species in a far-off jungle or on a ship in the middle of the ocean. I was not wearing a wide-brimmed hat under the blistering sun. Rather, I found a new species in a dark, windowless room in the Field Museum of Chicago, perhaps as far from the great unknown as can be.

I slept the night before in a hotel room and had a good breakfast prior to the mile walk to one of the great repositories of natural history in the world. The Field Museum serves as both a venue for the display of science and a storehouse of millions of objects recording the story of life on this planet. As a child I walked the marble halls of the Field Museum in awe of the great beasts of bygone ages and of the people who devoted their lives to deciphering the history of life. These trips inspired me to pursue science and to seek the unknown in the fossil record, to search the vast geology of the Earth for clues to the history of life, and perhaps to prepare humanity for an uncertain future.

Returning to the Field as a young adult and being granted access to the private storerooms of fossils was the fulfillment of a lifetime goal. I worked alone in the dim, quiet rows of cabinets. Drawers stacked well above my frame were filled with pieces of ancient worlds, recording animals that lived and died long before the most ancient mammal ancestor of humankind was born.

The decision to spend a sunny July day in Chicago in a dark, lonely room may seem strange at first. But within that room was the possibility of discovery and learning. To this day, few activities give me deeper joy than looking through drawers of fossils, each a potential discovery waiting to happen.

Most of the drawers, filled with fossils of fishes (my chosen organism of fascination), matched what I had read in books and papers by scientists with more experience and knowledge than I. However, one drawer surprised me. I noticed the rocks had a strange, almost purple hue. The fishes within these rocks looked like they had died yesterday, with the details of their anatomy clearly unravaged from geologic time. These rocks were from South Dakota, far from the traditional stomping grounds of fossil fish enthusiasts.

A bit of history here: Almost all fish paleontologists have worked in Europe, Australia, China, or the east coast of the United States. Much less has been done in the western United States. Therefore, I had never heard of fish fossils from South Dakota. The labels in the drawer had no names for the animals, only noting that they were found outside of Rapid City, South Dakota. I knew very quickly that I might have found fishes new to science.

Going from that initial discovery to naming a new species involved a lot of work -- it was nearly four years from the day I first saw the rocks before a description of the first of the new species in that drawer was published. In that interval, I devoted two years to examining each fossil under a microscope to understand the anatomy of the ancient fishes preserved within. I read widely on other ancient fishes to ensure that the species was indeed new to science, translating Russian, German, and French works written before my grandmother was born. I even purchased a Latin dictionary to create a formal Latin name for the new animal.

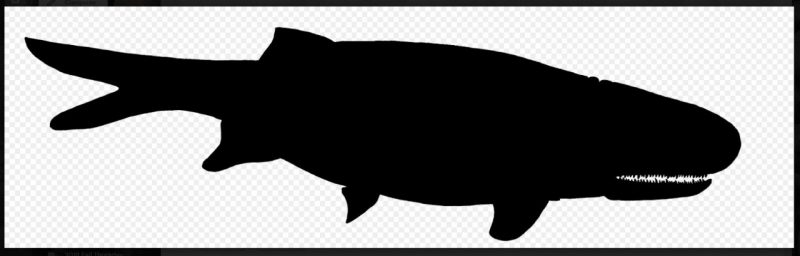

In the end, a new species of fish, Concentrilepis minnekahtaensis, was born. Don't worry about pronouncing that name; Latin is a dead language, so you can say it however you want. The name means "concentric scale from Minnekahta," referring to the concentric ridges of bone ornamenting the thick bony scales that cover the outside of the fish and the purplish rock formation the fossils originally came from. Even after the English language is lost to time, the timeless Latin phrase will carry those first observations to any researcher in the future.

Although the age of voyages of discovery is largely over -- for the best, I think -- one of the great joys of my life is that there are still new things to be found. Within the museums of the world are many new species, waiting to be recognized. To discover these animals is not only for the sake of curiosity. Only by understanding the history of life, and how life on Earth got to where it is today, can we predict how life will change in the future. Informing those predictions by history, both human and nonhuman, will ensure a better future for all.