Lindsay Hermanns: “A dunlin most dear”: Both emotion and data are useful in science

This narrative was written in 2021 by Lindsay Hermanns for GRAD 5144, Communicating Science, in response to an assignment to write a story about her research.

I think it often is easy to dissociate emotion and science. We scientists are information driven, looking for an explanation of what our data means, how it fits in the "real world." But this is a story of how emotions came barreling headfirst into my data collection. It serves as a reminder that our passions can intersect with our data in ways that should be revered and even sought after.

It was a time B.C. (before COVID) and the spring before my summer research began in Barrow, Alaska, where I would be studying shorebirds in the Arctic. Our small field team of five shorebird biologists were hunkered down between rolling sand dunes on the coast of South Carolina. The merciless coastal winds ripped sand up from the dunes and little grains gouged into our eyes as we scoured the landscape for wintering shorebirds escaping their northerly breeding grounds to seek (what they thought were) warmer temperatures.

Our team was here during late February, not an ideal time for a beach walk, with temperatures ranging between 30 and 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Feet were wet after slogging through intertidal pools as we conducted our bird surveys. Fingers were numb from the biting cold. Physical misery was present. We all had rosy cheeks peeking out of protective balaclavas and buffs.

But spirits were high as we began to set up our cannon net. This large, explosive-powered capturing device was used to shoot a wide-spanning net over flocks of shorebirds resting and feeding on invertebrates where the wash of waves meets the sandy beach in a froth. Dan Gibson, or Gibson, as we called him, had spotted the jackpot: A group of shorebirds unaware of our presence were making their way up to us along the intertidal zone.

The net was quickly readied, the explosives were set to launch the net, and then…we waited. Five minutes. Ten minutes. Gibson clutched the charge remote in his gloved hands, awaiting the “FIRE” command from our lead biologist.

The group of shorebirds skittered towards our “safe catch zone,” a place we had previously marked out with shells and driftwood about 60 feet from where we and our cannon net were silently perched. This zone allowed us to ensure that the net, once fired, wouldn’t physically harm the birds, but instead trap them under the netting.

My heart was racing. Once we fired the net, it would be an all-out sprint to the netted birds to untangle them, bring them back to our banding station, and begin our data collection of body weight and other physical indicators of fitness. We wanted to know how healthy the wintering birds were.

Finally, the group of foraging birds crossed the line of shells and driftwood into the safe catch zone.

I held my breath and my palms began to sweat as I waited to hear the command for Gibson to loose the net, reminiscent of anticipating the firing of the start gun during my high school track days.

“Is he going to make the call?” I wondered, as all 14 shorebirds finally entered the catch zone.

“FIRE!” I heard from our lead biologist, and a loud BANG! ensued as the projectiles launched the net into the cold blue sky and down upon our catch.

I leapt up, sand flying from my soggy shoes as I hit a full sprint along the shore down to where the net had landed over the small birds. Skidding to a stop next to the net, I began the careful, tedious, and painstaking extraction of each bird. As each was freed, I handed it to another biologist, who took it up to our banding station a few feet from where we had been waiting.

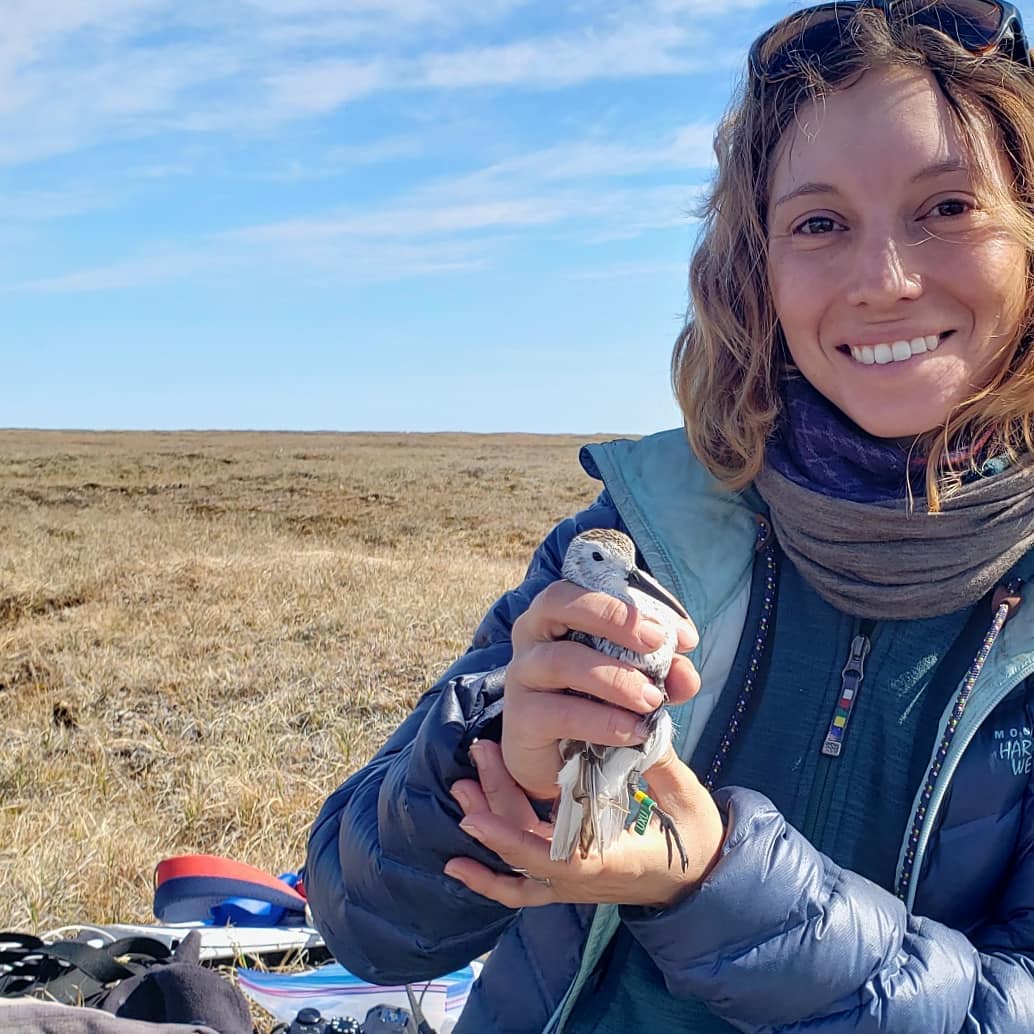

To my delight, one of these little shorebirds was a Dunlin, a species I would be studying in Barrow. I extracted it from the net delicately, pulling the small wings out of the net and working to untangle its legs without harm. I finally pulled the Dunlin loose, inspected it for injuries, and brought it up to the banding station myself. I measured it carefully, recording wing length, body weight, and feather wear on our datasheets. I put a small metal leg band on its left leg and a brightly colored orange band on its right leg to distinguish it from other shorebirds and help future biologists track it.

The crew worked diligently to process the shorebirds. Soon the science was done, and it was time to release them. I held the Dunlin gently yet firmly in both hands, turning it to one side and then the other, admiring the plain but beautiful winter plumage, the long glossy beak made for probing in the sand for food, the delicate build.

I looked into its eyes and unexpectedly became overwhelmed with admiration and love. This potato-sized bird would soon be flying up to the Arctic to breed, thousands of miles from where we had captured it that day. It would quite possibly reunite with its mate from last year to raise chicks. Hopefully, it would survive to make this same journey for many years over.

I marveled at this being. I pondered the perseverance of life in all forms, and my thoughts and emotions pooled into tears flowing freely from my eyes.

I relaxed my light grip on the Dunlin, and before it took flight, it sat there upon my open palm, wind ruffling mottled white and grey feathers, steadying itself on spindled legs. Suddenly, it opened its wings and caught the draft of the wind, gliding away through the air with interspersed rapid sharp wingbeats.

I turned to the crew after releasing the bird, wiping my tears away with a glove. Gibson looked up at me as he spooled the net and prepped it for our next catch.

“Everything okay?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said, cheeks still wet. “Damn sand, anyway.”

It has been two years since I first held my study species, and I carry that moment with me every day. It has helped me to remember that life of any form deserves our respect, that the biodiversity of our planet and the ability of living creatures to survive are inherently amazing, and that preserving that biodiversity and protecting living creatures is worthwhile. The memory reminds me that life of any form should invoke emotion, whether we are simply observing it from the backyard or collecting scientific data on our study species. We should take moments to marvel when we can.