Henrietta Bellman: Giving a flock about beach-nesting birds

This story was written spring semester of 2018 by GRAD 5144 (Communicating Science) student Brandon Dillon as part of an assignment to interview a classmate and write a news story about her research.

Boxer Muhammad Ali once said, “It’s just a job. Grass grows, birds fly, waves pound the sand. I beat people up.”

Unbeknownst to Ali, around the time of his death in 2016, Henrietta Bellman was beginning her journey in graduate school to study exactly what Ali had referenced. Not the beating people up, of course, but rather the grass, birds, and sand.

Henrietta Bellman, or “Hen,” as her friends call her, is a master of science student in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation in Virginia Tech’s College of Natural Resources. She’s part of a group called the Virginia Tech Shorebird Program, which studies coastal birds and their habitats in an effort to understand and promote their conservation.

With funding from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Biological Opinion), Hen studies a species called the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) on the barrier islands south of Long Island, New York. Her research focuses on the birds’ nesting responses to changes in the island before and after large storms, specifically Hurricane Sandy, which hit the barrier islands in October of 2012.

Plovers prefer to nest in sandy areas free of beach vegetation, Hen says, and will return to the islands year after year to reclaim their previous nesting areas or territories. As grass and other vegetation encroaches upon sandy nesting areas, birds must find other places to nest.

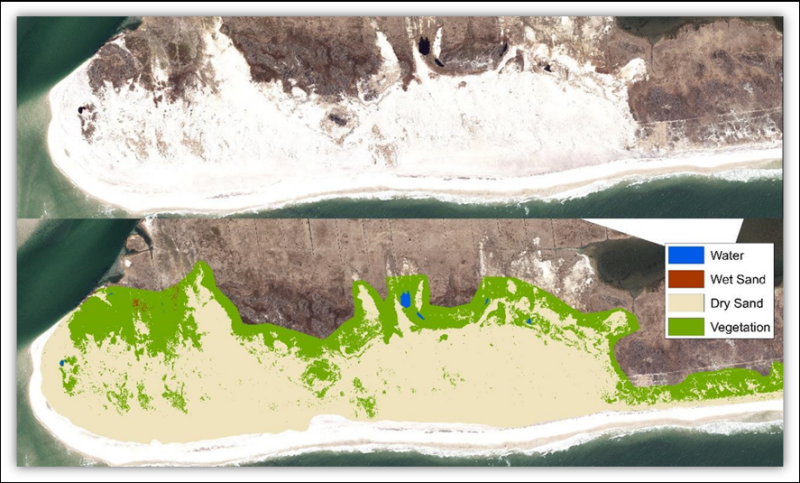

Hen’s work at Virginia Tech includes studying high-resolution photography and elevation surveys captured from airplanes. She uses this data to estimate and predict the plover population by looking at things like changes in sandy land cover.

But exactly how many plovers the island attracts is something airplanes and satellites can’t count directly. And because of that, Hen’s job also involves her traveling to these islands, where you might witness her briskly walking to and fro on the beach wielding a spotting scope or a butterfly net on the end of a long pole, capturing plover chicks. Her walk is brisk because the group has a “no running” policy to prevent the squashing of eggs—easy to do when the nests are right on the sand.

Hen captures chicks on the beach and adults at the nest, tags them with a leg-band—essentially a fashionable bracelet designed for a bird—and releases them. In the case where an adult has already been tagged, she records the bird’s bracelet ID with a note that this one has returned to the island from a previous year. Hen and her team, including three other Virginia Tech graduate students, also take body measurements from the birds (such as mass) and monitor the nests through the breeding season.

Hen tells me that so far it seems that the sandy habitats have attracted more birds as time progresses. The growth of these habitats can be attributed to two factors, she says.

The first was Hurricane Sandy. During that storm, water inundated areas that were normally dry. Waves rolled in over the beach, up and over the dunes, and finally came to rest in flat inland sections of the island. Known as overwash events, these inundations removed vegetation, which provided more space for the birds to claim as theirs during nesting.

The second factor potentially contributing to the population increase of the plovers is human restoration projects. Large expanses of sandy habitat, intended to mimic storm-created overwash, were created to offset barrier island stabilization projects. These stabilization projects aim to protect Long Island and New York City from future hurricanes and storms. Because the habitat-altering stabilization projects are in areas where piping plovers breed, and because the birds are a federally protected endangered, and state threatened, species, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are legally obligated to reduce impacts.

Hen’s research evaluates how these storm- and human-created habitats function, as well as whether the plovers use them (or not!).

However, Hen warns that if these storm- and human-created sandy habitats are not maintained through habitat management from land owners, they will quickly become revegetated, reducing nesting opportunities for this federally protected species. One of Hen’s research goals is to quantify the annual vegetation regrowth to help guide habitat management.

To learn more about the project, go to http://vtshorebirds.fishwild.vt.edu/.

All images courtesy of Henrietta Bellman unless otherwise indicated.