Frankie Edwards: Using simulation to study reversal of opioid overdoses

This narrative was written in 2021 by Frankie Edwards for GRAD 5144, Communicating Science, in response to an assignment to write a story about his research.

The participant sits across from me. I look down in front of me and see two pens, my interview guide, and a hot coffee.

It’s pre-Covid. The participant and I are unmasked. I have a video camera set up in the corner. A red light on the front indicates that it is recording.

I ask, “Can you describe the setting where a person who overdoses on illicit opioids is likely to be discovered?”

The interviewee fidgets uncomfortably. I can see them replaying the event in their head. I feel like a detective at the start of an investigation trying to piece together the description the interviewee gives me. However, I am not a detective. I am a graduate research assistant. I am conducting qualitative research by interviewing people likely to have witnessed or been the first on scene to assist someone experiencing an opioid overdose.

Opioid overdoses are significant public health threats. To date, opioid overdose mitigation strategies have primarily included mass distribution of naloxone, an opioid overdose antidote. Vulnerable populations like people with active opioid use disorder are in a unique position to witness an overdose and be the first on scene to assist persons who overdose.

I am a Ph.D. candidate in Dr. Sarah Parker’s lab at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute in Roanoke, Virginia. I am leading a research project on the simulation and evaluation of community opioid overdose response. Our work has consisted of interviews much like I described in the opening of this narrative. I am by no means a detective trying to figure out a crime; in fact, people who respond to an overdose by administering naloxone are in their legal right to do so. In recent years, state and federal governments have implemented Good Samaritan Laws. These laws vary from state to state, but at the core they protect the public and enable them to intervene during an opioid overdose emergency.

The project that I am helping with is innovative because we are developing an assessment tool that can be used to grade someone’s performance as they respond to an opioid overdose, like assessment tools used for cardiopulmonary resuscitation certification. The investigative interviews we conducted helped us generate a preliminary version of this assessment tool.

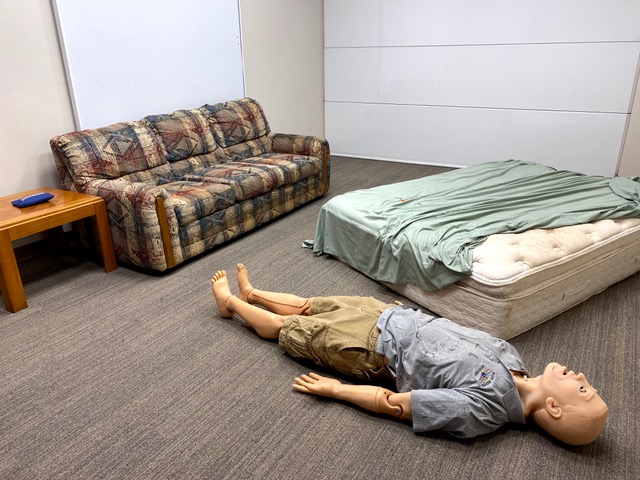

Additionally, the project that I am helping with includes testing the use of this assessment tool via high-fidelity simulation. I have often used the analogy of an escape room to describe this. We used the evidence gathered from our interviews to conceptualize an environment and construct a room that looks like the scene of an opioid overdose.

How do you re-create an opioid overdose for assessing performance? Great question! We use a sophisticated life-like manikin. We call him Hal. Hal can be remotely controlled, and his vitals, such as breathing and pulse rate, can be modified to match that of an overdose victim. While a study participant is reversing Hal’s overdose, we can correct Hal’s vitals. This allows participants to adjust their response according to the changes they observe in Hal’s vitals.

Simulation is cool because it provides a controlled environment without risk to participants. In addition, high-fidelity simulation can offer the option to video record, thus allowing me and others on our research team to analyze behaviors after the simulation.

The goal of our current research is to validate the tool we’ve generated from the evidence gathered in our previous research. Before we can make inferences on individuals’ proficiency at responding to an opioid overdose, we must validate our assessment tool.

A key component to validating any behavioral assessment tool is acquiring high levels of inter-rater agreement. Essentially what this means is that we compare the scores that multiple evaluators give participants. Fortunately, we’ve acquired an acceptable level of inter-rater agreement.

Moving forward, we must continue validating our assessment tool. My research team’s next steps are to survey board-certified emergency medicine healthcare providers to determine which items on our tool are clinically important. This will help with scoring participants and making inferences on their proficiency.

I am passionate about this work because I hail from southwest Virginia. I’ve known people who’ve been the victim of opioid overdoses, and I hope to contribute something meaningful to positively impact the opioid epidemic.