Esther Oyedele: Looking from space to understand what’s beneath our feet

This piece was written in the fall of 2024 by GRAD 5144 (Communicating Science) graduate Esther Oyedele.

In late 2020, I packed my bags and left Nigeria, crossing the Atlantic Ocean to pursue my dream of graduate study in the United States. I had studied geophysics as an undergraduate student and spent time working in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry, but I found myself wanting something different. I wanted to work on projects that could make a positive environmental and human impact, so I set my sights on studying how water moves and changes on and beneath Earth’s surface.

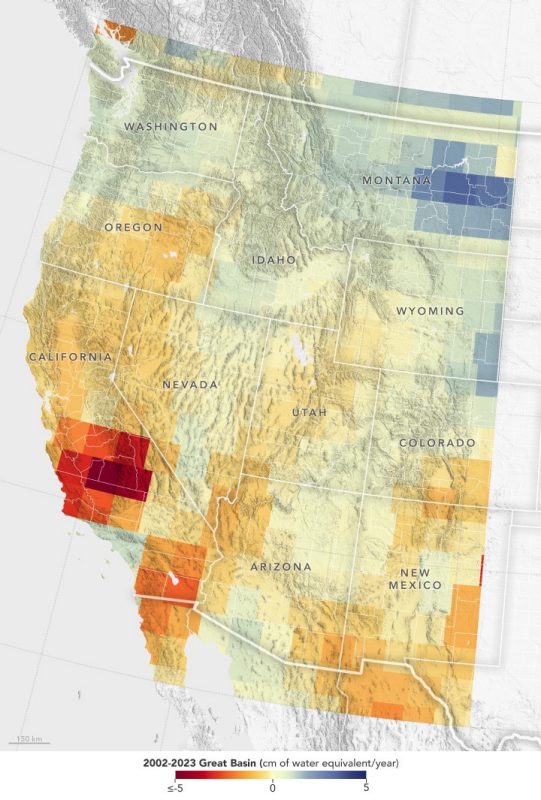

My first project in the United States was a master’s degree study focused on Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the United States, located on the Nevada-Arizona border. I used satellite technology to look at how water levels in the lake affect the land around it. This lake, which supplies millions of people with water, rises and falls with rainfall, drought, and water use. Working on the project opened my eyes to how crucial water is in the American Southwest, and I became fascinated by groundwater, the underground water that serves as a hidden but essential lifeline for people, farms, and nature.

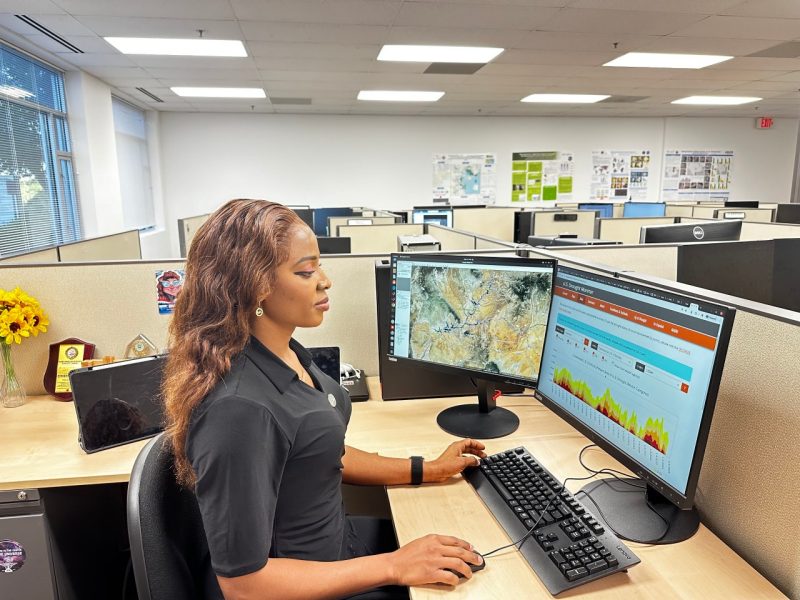

Now, as a Ph.D. student, I study groundwater in one of the driest regions in the United States, the Colorado River Basin. This basin provides water to over 40 million people, but it’s facing a serious shortage as climate change, droughts, and increased demand continue to take a toll. My research uses earth-observing satellite data to track how much groundwater is left and where it’s being lost. Some of these satellites help us see underground water by measuring small shifts in Earth’s gravitational field, giving us clues about where water levels are dropping. Isn’t that remarkable? We look from space to understand what’s beneath our feet! These satellites show where our hidden water is running low and the areas most at risk.

Groundwater might be out of sight, hidden under our feet, but it plays a big role in supporting communities and ecosystems, especially in regions prone to drought. By bringing this hidden resource to light, my work contributes to sustainable water management practices in the American Southwest.

It’s been a big shift from working in the oil fields to studying water, but I’m grateful to be part of work that contributes to a more sustainable future. As water security becomes one of our most urgent challenges, I’m excited to keep learning and uncovering what we can do to protect this vital resource.