Erin Poor: Scads of scat and no big cats--the challenges and rewards of collecting field data

The following story was written in April 2018 by Savannah Leeah in ENGL 4824: Science Writing as part of a collaborative project that included the English department, the Center for Communicating Science, the Fralin Life Science Institute, and Technology-enhanced Learning and Online Strategies (TLOS).

Imagine you are backpacking through a Sumatran rainforest. All of your belongings are in a 30-lb pack on your back. You are covered in leeches and dripping with sweat. You have little contact with your friends and family. Perhaps worst of all, you’re surrounded by men who are unconvinced you’re fit for the job.

For some this may sound like the plot of a movie, for others a nightmare, but for Erin Poor it was her reality for two years.

Poor is a Ph.D. candidate in Virginia Tech’s Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation. Her work is focused on forest degradation in Indonesia and its effects on the lives of the big cats who live there.

As long as Poor can remember, she has loved being outside, a love that was fostered by her parents. Ultimately this love for the outdoors led her to abandon her pre-med track at her undergraduate school and pursue a career that better accommodated her passions.

“I thought I was going to go to med school until I realized that I had been brainwashed by my parents to love the outdoors,” Poor explained with a laugh.

After earning her B.S., Poor got her master’s at Duke University and began working with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). “I knew I loved Southeast Asia and big cats, so I asked my boss [at WWF] if he knew of any research opportunities there and he suggested Marcella Kelly at Virginia Tech. It just kind of happened serendipitously,” Poor said.

She reached out to Kelly and gained a position as a graduate student studying big cats in Indonesia. From there Poor was on her way to Sumatra.

Poor’s primary concern is the decrease in size of forests in Sumatra and the effect that has on cat species.

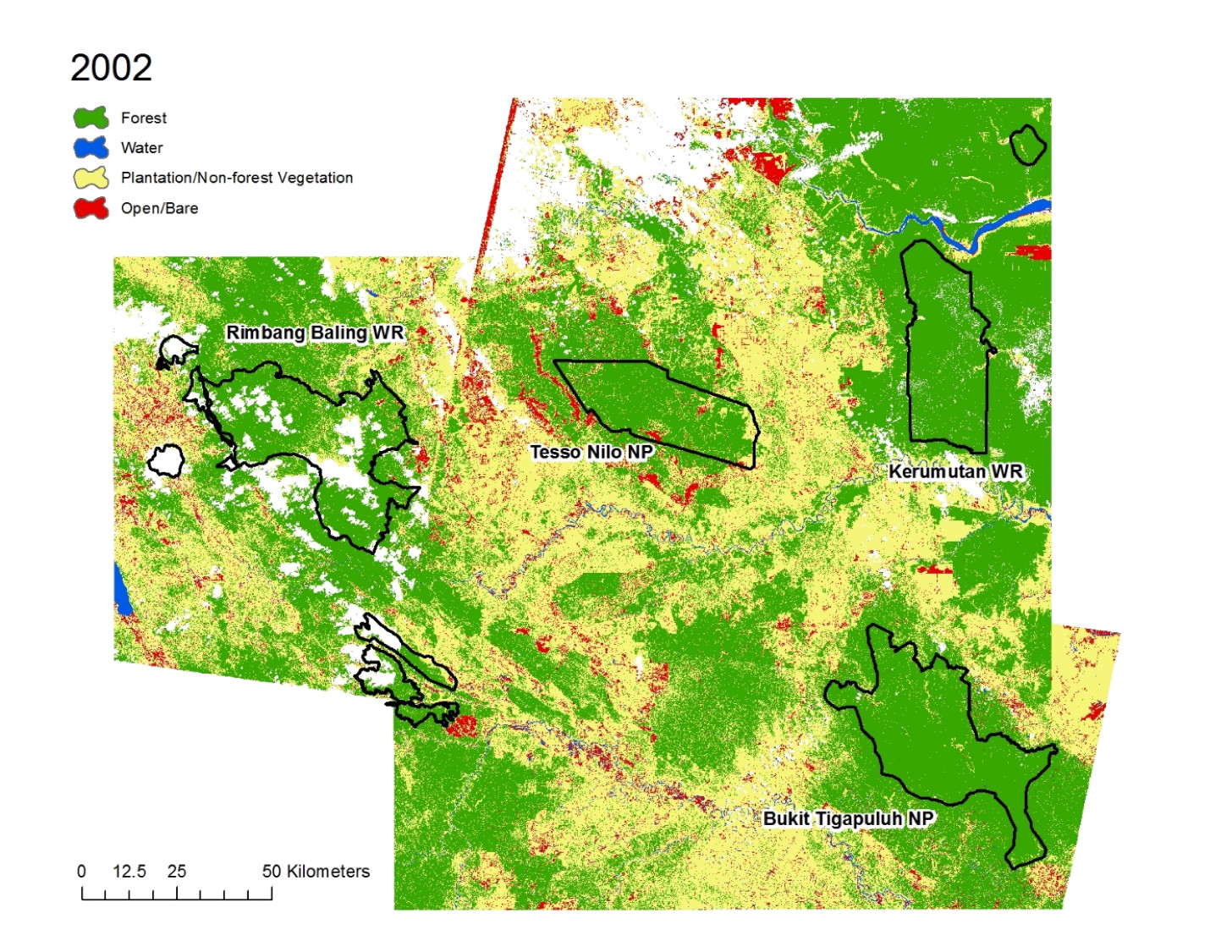

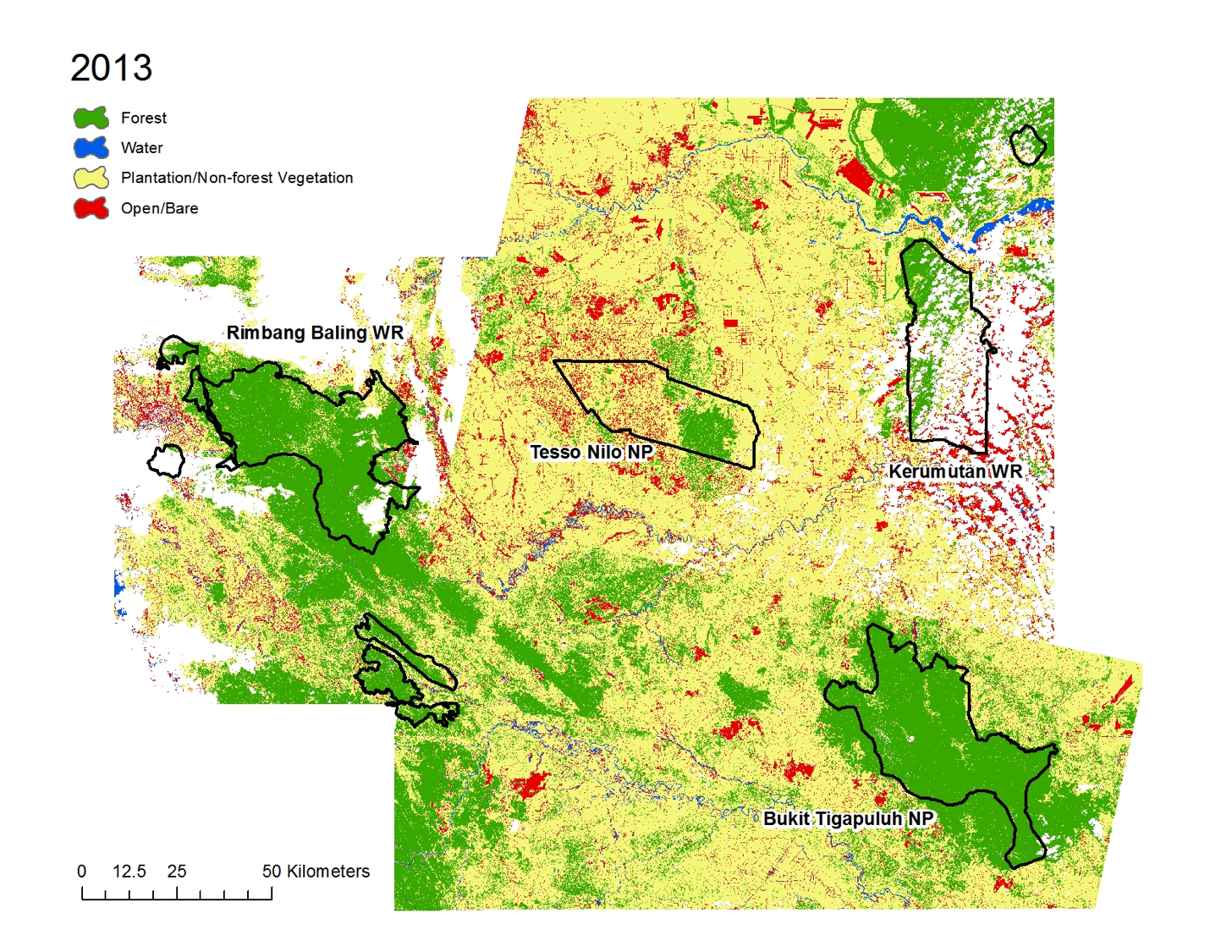

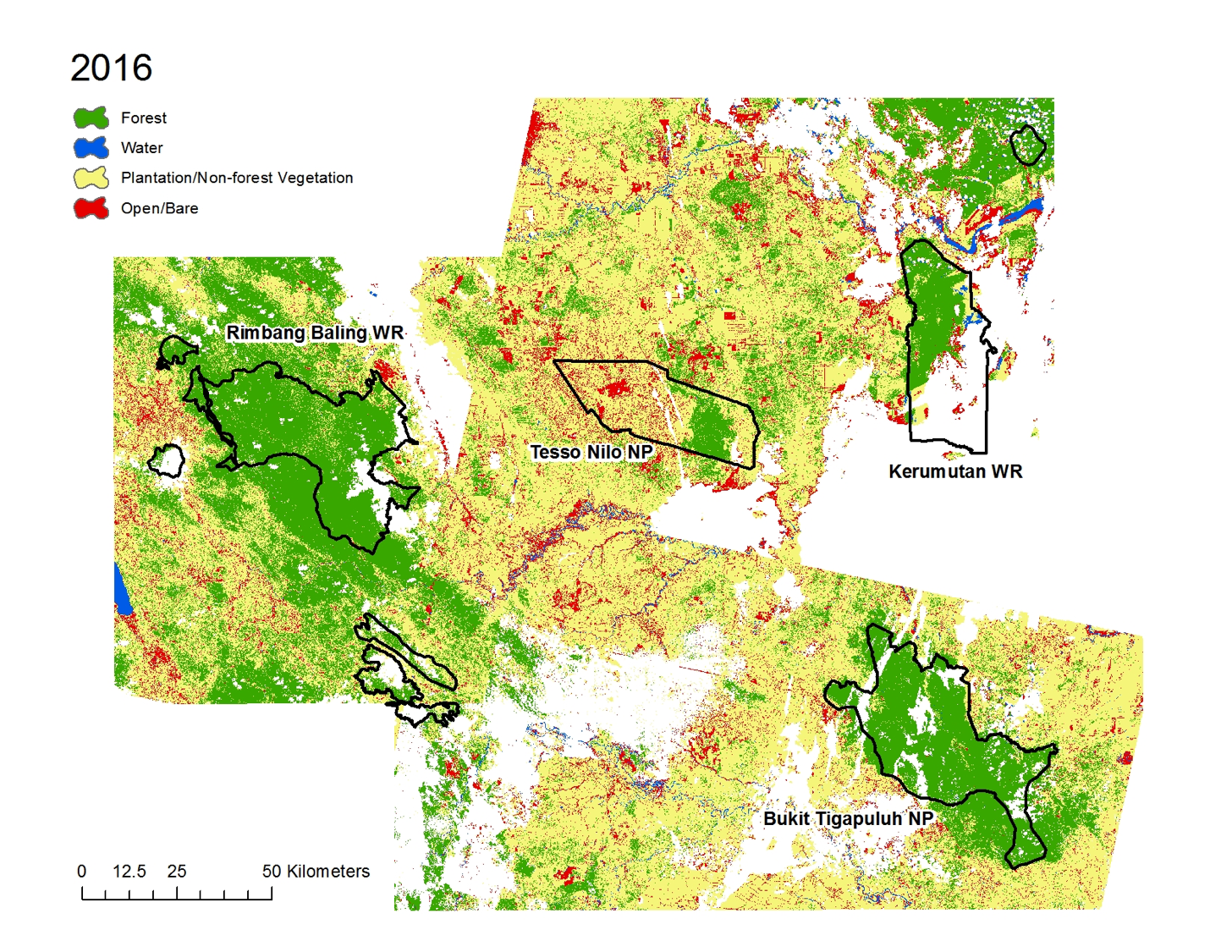

“In Tesso Nilo, a national park in Indonesia, they’ve lost over 60% of natural forest. There’s also 2,400 km of roads in that national park. So that’s like from here to Denver. These results are much worse than I had hoped,” Poor said.

Tesso Nilo is an important mid-point between the mountains and lowlands of Sumatra: forest degradation in Tesso Nilo means the big cats of Sumatra are unable to travel between the two areas, which can increase inbreeding and thereby speed up extinction.

According to Poor, the forest degradation is largely due to oil palm plantations. Twenty percent of the world’s oil palm is grown in Indonesia. Deforestation for oil palm is illegal, but officials in Indonesia are susceptible to bribery and do not enforce the law as firmly as they should. This makes Poor’s job of convincing the government of the importance of conservation difficult. Poor intends to give her findings to the Indonesian WWF office and the government, who will hopefully create a plan to stop deforestation and restore the forests of the country.

The primary way that Poor tracks deforestation is through land cover data. Poor and a team of Indonesian citizens embarked on 10-day treks in the rainforest, mapping parts of Sumatra. Poor was able to work with this group because she had previously spent some time in the country learning Indonesian. Despite this, she faced some language barriers because of the use of local languages.

Now Poor is working on comparing the data they collected “on the ground” to older satellite images to track how much deforestation has occurred.

“I think the situation is extremely urgent,” she said. “I’m hoping to provide maps and recommendations that the government can use.”

The other data Poor collected in Indonesia were scat samples of tigers, clouded leopards, Asiatic golden cats, marbled cats, and leopard cats. Lab work on these samples allows Poor to see the effects of deforestation on the cats by tracking genealogy and inbreeding. Genes are important, particularly for tigers, since there are only 300 tigers left in Sumatra. If the gene pool gets too small, tigers will be that much closer to extinction. Poor’s work with the scat samples is much slower than her work with land cover, though, because all of the lab work has to be done in Indonesia. She relies on her partner in Indonesia to send her the information as it comes in.

Despite her intense interest in big cats and her close work with cat scat, Poor never saw a cat in the forest herself. Some people, she says, can work in the area for 10 years and never see a cat. But instead of expressing dismay about this, Poor’s face lights up when she is talking about the wildlife she did see in the Sumatran rainforests: “I didn’t see any cats, but I did see monkeys, elephants, and a colugo [similar to a large flying squirrel],” Poor said.

The deforestation occurring in Indonesia is very important but certainly not unique.

“I’ve been trying to frame it as a global societal problem,” says Poor, who sees how her work fits into a larger global context. “Tigers have important cultural meaning and they’re important for ecosystems in general. We can’t let this gene pool die out.”

As though being sweaty and covered in leeches wasn’t enough, Poor also dealt with major sexism in the field.

“Their [the Indonesian’s] perception of white women was from movies, and white women in movies are…not the type to go backpacking for ten days in the rainforest,” Poor said. “It’s all men in the field there with very traditional gender roles. I always had to explain what I was doing and why. Anywhere I went I would be stared at. I was followed occasionally…I was grabbed on my motorbike once,” she explained.

Despite all of these challenges, Poor is still enthusiastic about her work. “I definitely wanted to quit multiple times, but I’m stubborn,” Poor said with a laugh, “I can’t think of anything more challenging or more rewarding.”

As Poor looks ahead, she sees the value in communicating her findings and views that as the next step in her process.

“Not enough scientists share their work. If the public doesn’t know about what we’re doing and the issues we’re trying to solve then I don’t really know how the problem is going to be solved; we’re just publishing our work for a bunch of other scientists,” Poor says. For her, this means spreading her work to the Indonesian government, WWF, and anyone else that needs it, so that they can use it to help curb deforestation for the good of the Sumatran big cats.

Poor understands that she can’t force anyone to take her research into consideration, but if Poor’s determination (and, by her own words, stubbornness) in her field work is any indicator, she won’t rest until the forests and the big cats of Indonesia have a better future.