Bailey Howell: Learning from lizards

The following story was written in December 2021 by Elizabeth Boyer in ENGL 4824: Science Writing as part of a collaboration between the English department and the Center for Communicating Science.

Bailey Howell loves lizards. Her affection for the reptiles is clear from the way she talks about them, from the silver, lizard-shaped ring she wears around her index finger, and from her research focus: She studies the evolution of traits in lizards, specifically how lizards evolve adaptations for survival in urban environments.

Howell grew up chasing lizards around her hometown of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Although she thought she grew out of her interest in the creatures, her childhood primed her for what was to come. In her college years at Mississippi University for Women, Howell was focused on her biology degree. One day, a professor visited her class in search of an assistant.

“Basically, his pitch was, ‘I’m studying lizards and their sticky feet, and I want a student to help me,’” Howell remembered. Knowing that she could benefit from the research experience, Howell signed up. The research rekindled her interest in lizards, “and I just fell back in love with what I had found my love for as a child,” she stated.

After this research stint ended, Howell studied other things for a while. “But I just missed what I was doing; I missed the lizards,” she said. “I missed studying their [evolutionary] tree, and how they changed in different environments, and the like.”

Now, as a second-year Ph.D. student at Virginia Tech, Howell wants to know how urban environments affect the evolution of lizards.

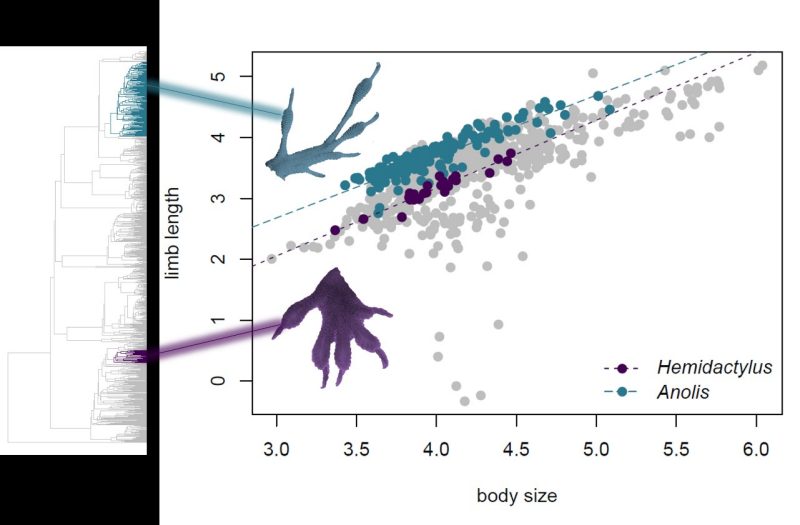

“I'll try to see how [the lizards and their traits] evolved throughout the past,” Howell explained. “When you try to see how it has evolved, you get a rate of evolution, which is how quickly the trait has changed through time.”

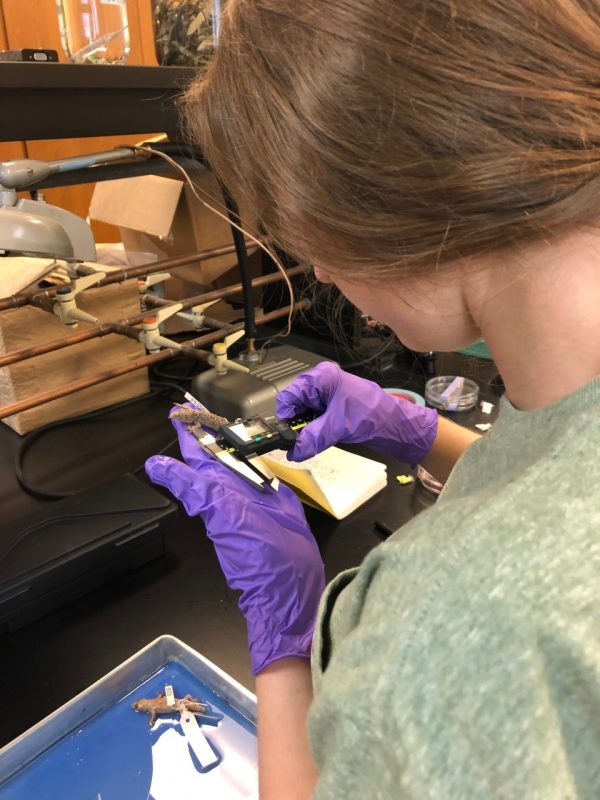

To get this look into the past rate of evolution in lizards, Howell studies charts of lizard evolution, called phylogenies or trees, that have been created by other scientists. The phylogenies she uses show how different types of lizards are related to each other. Instead of showing connections between individuals, like a family tree, they show how different species are related to one another. Sometimes she visits museums to observe and measure the preserved bodies of lizards.

After gathering data about the past evolution of lizards, Howell’s goal with the two groups of lizards she studies is to “see if one group, with regards to a certain trait, has changed more than the other, and if that is going to influence how quickly those traits change out in the wild, between urban and forest sites.” Explaining further, Howell stated that “you can actually go out and measure the traits and then see how they've changed in an urban environment versus a natural [environment].”

Howell aims to do these kinds of hands-on observations later in her research by catching and studying lizards in Florida cities. For now, Howell says that “a very large portion of my time is using computer models. A lot of what I do is fine tuning or comparing models and computer work.” These models use phylogenies to “statistically reconstruct the history of the organism’s traits and to give back a rate [of evolution],” according to Howell.

Despite the electronic nature of much of her work, Howell’s research has very real applications.

“There are species that can survive in an urban environment and that do survive and live in an urban environment very successfully,” she explained, “and those species really interest me because that's not true for a lot of animals.”

Howell’s work in the evolutionary history of lizards allows her to make predictions about the effect of urbanization on lizard populations. The data she gathers could, in the future, aid scientists in figuring out why some animals, such as squirrels or pigeons, thrive in urban settings, based on how they changed throughout the past.

“To my knowledge, there isn't anyone doing that” for lizards, Howell said, so her studies could pave the way for more research in this area. To anyone who talks to her about the creatures, one thing is clear: Howell’s love for lizards is contagious.