Ama Essuman: On burnout, hard work, resilience, and perseverance

This piece was written in the spring of 2024 by GRAD 5144 (Communicating Science) student Ama Essuman as part of an assignment to write a story about her research.

This is a story about my master’s level project. I call it my story of resilience and perseverance.

It all started after my first year of M.Phil. education. In my institution, the first year was dedicated solely to academic work, while the second was for a research project in a lab. I had to submit a thesis at the end of the second year and defend it to qualify for completion and graduation.

I was in a renowned scientific institution in West Africa. When I say “renowned scientific institution,” I mean “an institution with a very competitive spirit,” one in which success was judged by your ability to complete a somewhat complicated project within the required time frame — and a place where excuses for a poor or stalled project would not cut it. Ultimately, a publication in a highly respected journal meant you were excellent.

Subconsciously, everyone — including me — was under pressure to prove ourselves worthy to be a part of the institution.

In my second year, I began my ambitious project. This project was based on my interest in infectious diseases and how they could be cured. I was pursuing a project in drug discovery, searching for a hit compound (a compound with a desired activity during screening, which has the potential for further development) for the infectious parasitic disease Leishmaniasis. My potential drugs were all synthesized plant-based compounds. I had it all planned out perfectly, from a well-established hypothesis to the main objectives I planned to accomplish within one year of research.

The main hurdle was finding an active compound that would pass Objective 1 of the research. Objectives 2 and 3 were centered on finding out how this active compound works. I eagerly began this research by screening the six main target compounds. Based on the preliminary data supporting my hypothesis, I was 99 percent certain that at least one of them was going to pass the first objective.

I was right: five of the six compounds had activities outside the range we were hoping to classify as active, but one — my savior compound, let us call it Compound 3 or C3 — was right where I needed it to be. This was going to be the key to progress with my project.

Then came the turning point that tested my resilience and perseverance. I found out, soon after I had discovered activity from C3 against the parasite, that C3 was one of the compounds not available in abundance for further screening. This felt like a stab to the chest. I was running straight into the ditch of a stalled or possibly failed project.

I had an urgent meeting with my supervisor, and we agreed that I needed to screen more compounds that were abundantly available in the lab. The isolation of C3 from its plant source or a synthetic production of it was going to take months, which I didn’t have. Every moment counted if I were to finish this research on time.

The other compounds that were available in the lab supported my hypothesis, but only weakly. Thus, the possibility of getting a good hit was highly uncertain, but I zoomed in anyway, hopeful.

I had no idea what lay in wait for me.

Let me throw some light on what Objective 1 looked like, just in case you’re thinking it’s too easy to complete. Objective 1 had three main experiments, the first a prerequisite for the second and the second a prerequisite for the third. Any compound that was to move further needed to pass all three stages. Failure at any level meant that the compound could not continue the journey.

The first experiment involved screening the compound against the parasite to determine the effective concentration (lowest concentration) of the compound needed to kill the parasite. The second involved screening the compound against human cells to determine the lowest concentration of the compound that would kill human cells. An ideal compound that passes the first two experiments is one that kills the parasite at a very low concentration and either does not kill the human cells or kills human cells only at a very high concentration.

I knew I should be able to complete these first two experiments within two weeks of intensive work, screening 10 compounds or even 15 if I pushed myself. The third experiment was a confirmation of the first. If the compound was truly killing the parasite, I should be able to show under the microscope that in the presence of the compound, the parasite dies.

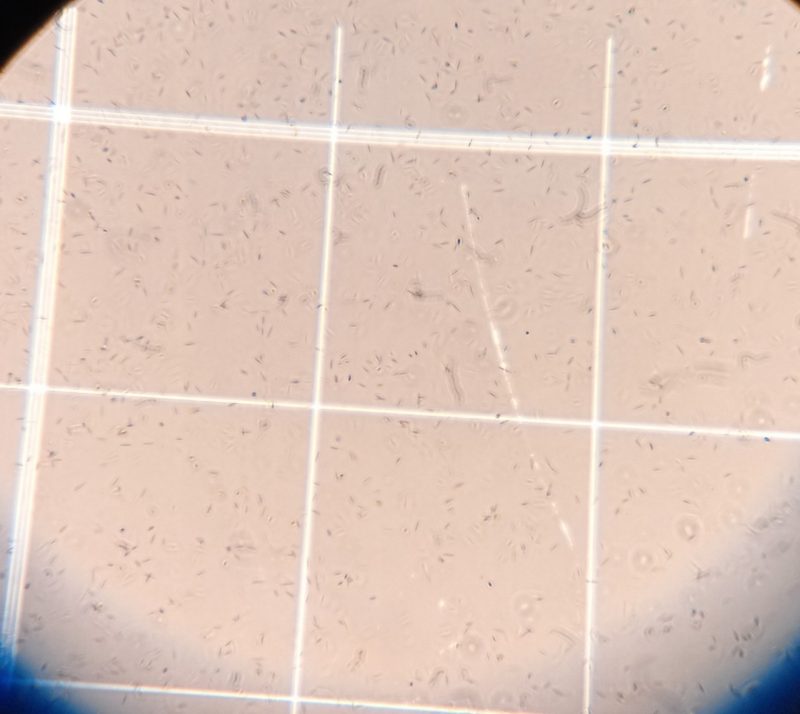

This experiment involved treating a specified number of parasites with four different concentrations of the compound, increasing concentrations of the lowest concentration identified in Experiment 1, and then counting the number of surviving parasites under the microscope for the next five days. This is followed by a recovery, where the compound is removed and the parasites are counted for the next three days. This would show whether the parasites were being completely killed or just disabled.

Fun fact: These parasites are motile, so you need to be fast and very precise. The ideal compound here that passes is one that completely kills the parasites within five days without recovery in the subsequent three days. The usual me should be able to count 48 samples with ease in a day. From experience, I knew that if a compound is not as strong in Experiment 1, it will most definitely fail Experiment 3.

After close to two months of continuous work, stretching myself without breaks, I ended up screening 54 compounds through Experiments 1 and 2 because I needed to get as many active compounds as possible, with the hope that at least one would pass Experiment 3. This was a tedious process, but I had six compounds that passed Experiments 1 and 2. They were ready to move to Experiment 3.

The worst was still to come. I began work on Experiment 3 with two compounds at a time, which meant counting about 96 samples in a day. I would start at 7 a.m. and finish at almost 8 p.m., most days without breaks. The complete experiment lasted for eight days, and then I would immediately hop on to the next set of compounds.

Imagine having to count 96 samples of motile cells every day, only to find out on Day 3 or 4 that the cells have been contaminated by fungi. This contamination means your results will be unreliable and that you have to discard all of the hard work and start over again.

This was my story for the next close to three months. I was exhausted. There were times when I felt like the whole world would collapse in on me and it would all end. But I could not stop. I had to keep going. I needed to succeed for my mental health. I am usually that person who is afraid of giving up. When I set my mind to achieve a target, no matter how long it takes, no matter how often I come across setbacks, I have to meet it. It gives me joy. It gives me fulfilment knowing that I am able to meet my goals.

Most importantly, I felt that my supervisor was counting on me to succeed and that there was no room for disappointments. My inability to succeed would mean feeling that I did not belong in my institution, where everyone worked hard and the proof of that hard work was that you produced results. I was possibly going to break down, but my mind would not allow it.

When I thought all hope was lost because I was finally completing Experiment 3 for my last set of compounds without good results from the previous ones, the tides finally changed in my favor. While searching for a reagent I needed, I came across a sealed box that contained compounds I had not yet worked on. As I sorted through these compounds, I came across C3, my savior compound that had already passed Objective 1. It was sitting right there, stored away and forgotten about, enough quantity to move forward and possibly complete my project.

All the emotions that had refused to come to me came running with the speed of light through tears (and I hadn’t called for them). For the next five minutes, I sat shedding silent tears of relief. I knew my days of exhaustion were over and that I could finally move forward with my project.

That was when I realized that I was mentally tired and really needed to take a break from my research.

After learning about the awful experience of my supervisor in graduate school, I picked up a few principles that I am working on applying in all my future research. I learned that it is okay for things to go south in research; you learn from such setbacks. Based on the research question, everyone will face peculiar challenges. Our timelines may differ, but that should not be an assessment of hard work. Most importantly, it is okay to take breaks and time-offs. It helps you think clearly and re-strategize, and it prevents burnout or loss of interest.

Fast forward: I was among five students from my class to graduate. The remaining students, I learned, were facing challenges with their research, so they were scheduled to complete and graduate later on, which is okay. What matters is putting in the effort and following where the research leads you.