Alexis Hruby: Shaking up the industry through new cow diets

The following story was written in April 2021 by Erin Slezak in ENGL 4824: Science Writing as part of a collaboration between the English department and the Center for Communicating Science.

Dairy is essential in the United States. Americans get a substantial amount of their calcium and Vitamin D from dairy products, and without our dairy cows, American health would change drastically. But, as the ones who take care of them, are we as concerned with the nutrients cows get in their diet?

Protein, a primary component of a cow’s diet, is made up of amino acids, which all contain nitrogen. Amino acids are essential nutrients, meaning that we cannot survive without them, but in high amounts nitrogen can cause harm to the environment. And unfortunately, when it comes to nitrogen, cows are only 25 percent efficient: 75 percent of whatever protein they consume is lost in the manure pit. If we relate that to money, 75 cents of every dollar farmers spend on protein is wasted.

Part of the problem is that cows are complicated animals. Their digestive system is a complex labyrinth of four stomachs and living microbes, which allows them to digest grass. The complexity of this digestive system means that scientists still have a lot to learn about cows, nitrogen, and waste.

Enter Alexis Hruby.

Hruby is a fourth-year graduate student in Virginia Tech’s Department of Dairy Science. Her interest in cows began when she was a child on her grandparents’ ranch in South Texas. Hruby works with a team of three other graduate students and five to six undergraduate students. They are all working to solve the same problem but are exploring different areas of research within it. By tackling different areas of focus within the cow diet study, they hope to make strides in determining the perfect diet formulation for healthy, high-producing cows with low nitrogen emissions.

Models for effective diets are constantly changing, with researchers trying to find that “sweet spot” in the formula. Diet guidelines are listed in the Dairy National Research Council (NRC), a book only published every ten years or so and, Hruby says, essentially the cow diet Bible.

“[In the current NRC guidelines] protein is fed based on a rough calculation called crude protein, which is a function of the amount of nitrogen in the diet,” Hruby explains. “Nitrogen is a part of all amino acids, which make up protein, so you’re roughly calculating how many amino acids are in [the diet].”

Hruby is studying what specific amino acids are needed to meet the requirement for cows. If she can crack the code and give farm nutritionists exact amounts of which amino acids are necessary for each cow, farmers could feed their cows the correct amount and lower their nitrogen emissions.

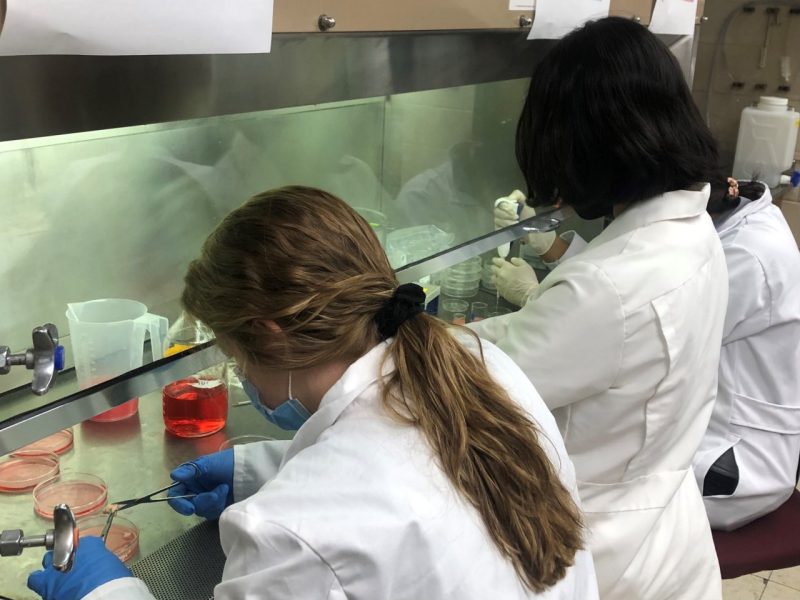

The main focus of Hruby’s research is testing out how different amino acids interact with each other within mammary epithelial cells (the cells that make up milk tissue in the cow’s udder). The cells she is using are ones she learned how to grow herself.

“Growing the cells has been an interesting experience. It’s probably not the most exciting thing, but you can run a lot more experiments on the cells as opposed to actual cows,” Hruby explains. “You can order cells from somewhere, but then you don’t really know how old they are or what cow they came from, so we have our own cell library that I was trying to make.”

Hruby recounts that when she first started the process of growing cells, she was simply given a cow udder in a bin and basic instructions from someone who had tried to do the process before.

“Obviously, the first time you try things, it’s not going to be ideal,” she says. “When you work with cells, for example, you could be concerned about contamination. In the beginning I had a contamination issue, but then I was able to sort everything out; I found a new anti-fungal and then I perfected the method. It just takes time and experience with these types of things.”

Hruby now has a first-author abstract for methods for growing the cells, which should help others who want to use her methods in their own research.

Hruby understands the many different impacts this research could have on the dairy business, from saving farmers money to creating a more sustainable industry.

“There’s a lot of pros,” Hruby says. “When you’re talking to a farmer when milk prices are low and they’re having a hard time making money, they’re trying to at least break even with the amount they’re spending at the farm. The farmers get virtually no support from the government, so they have to focus on the amount they’re making or they’ll go out of business and lose their livelihood. Strides we make related to nitrogen efficiency need to both save the farmer money and help the environment.”

Hruby’s colleague, Jacquelyn Prestegaard, recently conducted a trial in which she tested the effectiveness of three different cow diets: one based on the Dairy NRC, one intended to maximize farm profits, and one that was nitrogen efficient. By testing the cow’s urine, Prestegaard found that the nitrogen-efficient diet still kept the cows as healthy as they would be on the Dairy NRC diet. Two abstracts have already been submitted on the findings, one by Prestegaard and one by Hruby, so that they can share their research findings.

Hruby attributes a lot of her success to the hard work of the other graduate and undergraduate students on the research team.

“Although I have a great advisor, I think having a good team contributes heavily to my experience. They’re the ones that have either run experiments similar to yours and will directly train you or they will just help you a lot as collaborators,” Hruby says.

Hruby’s current goal is to continue her research with the cell trials she is conducting. She plans to take the results she gets from studying the cow cells and experiment with the findings next spring on live cows. She plans to do this by formulating diets based on the findings from her cell research. From there, she’ll see how cows react to the diet by assessing their health, milk production, and nitrogen efficiency. She also wants to become a nutrition consultant for dairy farmers. In that position, Hruby can apply all she has learned in her research here at Virginia Tech to improve the dairy industry from the inside.