Ed Yong Visit Prompts Discussions on Science Communication, Ethics

December 12, 2022

The fields of science and journalism are often seen as separate spheres. While many acknowledge that their brief intersections are beneficial to both professions, it isn’t often that the contributions of such collaborations are brought to attention. At the Center for Communicating Science, these are precisely the interactions we want to highlight.

Ed Yong, science journalist and writer for The Atlantic, visited Virginia Tech October 18. During his visit, he led two hour-long sessions – one for campus communicators and another for graduate students – as well as giving a public lecture at the Moss Arts Center. His lecture, “The Art of Science Journalism,” discussed his experience in reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Throughout his visit, Yong gave useful advice about journalistic integrity, his philosophy regarding his work, and how one can be successful in the field of scientific journalism.

One of Yong’s most insistent points was the ethics of his work. Both scientists and journalists “have a tradition of seeing themselves as unbiased, neutral, objective, and producing truth,” Yong said. “This is pernicious and dangerous and should be challenged at every opportunity.”

Journalism, specifically that regarding scientific concepts, is prone to inaccuracies. It takes interviews from multiple sources as well as a fine-tuned understanding of each interviewee to ensure the correct conclusions are drawn, Yong explained.

“I continue asking questions until I feel I have a good understanding of their point,” Yong said. “Then I may use their responses in future interviews to compare viewpoints.”

The curiosity he possesses about the topic is the primary drive for each article. Yong emphasized this with anecdotes about interviews he had conducted, many of which centered around sensitive topics and marginalized populations. In one of his most recent articles, for example, Yong wrote about those living with repercussions of COVID-19, termed “long COVID.” Readers praised him for not only reporting on the topic, but doing so with such sensitivity and care.

While treating people he interviews with respect and compassion, Yong also points out the importance in choosing the correct subjects for his interviews. Having input from diverse individuals gives him a range of information, including that which people from different backgrounds may not understand. To ensure representation, he personally tracks the number of women and BIPOC he includes in his pieces through quotes and citations. Additionally, his rule of thumb in recruiting new viewpoints involves ensuring half of the people he interviews are people he has never spoken with before.

The flip side of interviewing is being interviewed, and Yong encourages journalists and scientists involved in research to know the responsibilities of their positions before being involved in an interview. While it may seem otherwise, the researcher is the one holding the power, he says. They may refuse to answer questions, redirect or rephrase questions, and bring up points they feel are pertinent to the conversation even if the interviewer does not explicitly ask about them.

“If you hang up, I’m screwed,“ said Yong. “It’s in my best interest to be a good and an ethical interviewer.”

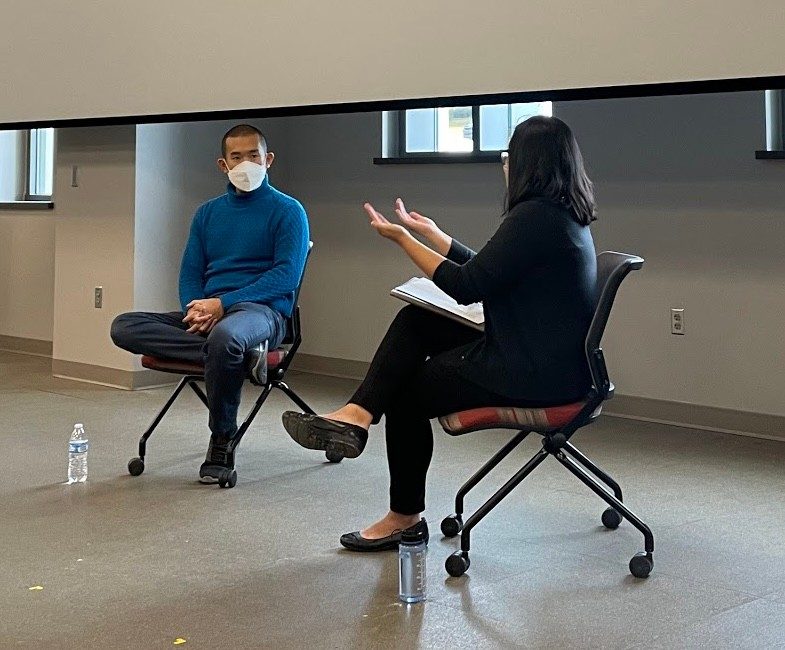

During a session for Virginia Tech communicators, moderated by campus communicator Eleanor Nelsen, Yong and one of his sources, engineering faculty member Linsey Marr, conversed about the importance of explaining scientific research clearly. When asked what makes a researcher a good source for one of his stories, Yong replied that a combination of intellectual rigor and humility is the sweet spot. He likes to hear someone say “I don’t know“ or “We don’t have a definite answer for that yet, but we are working on it.“ He appreciates researchers who recommend other experts and who “stay in their lane“ instead of trying to provide information about something that is not their area of specialty.

In the graduate student session, attended by approximately 60 students from varying disciplines, Yong advised journalist-hopefuls to prepare before attempting to tell a story. This, he says, is the key to avoiding the dreaded writer’s block. With interviews conducted, background research performed, information and quotes organized, and a thorough outline of the story at the ready, sitting at a computer not knowing your next step is nearly impossible.

Yong also acknowledged that storytellers, journalists or otherwise, have an obligation to tell their stories on the platform that they prefer. However, once a platform is chosen, there is a responsibility to consume that exact kind of media. In this way, he says, writers will get a sense of what is engaging, what information is imperative, and what can be excluded. From Twitter to magazine articles, storytellers must adjust their communication style to accommodate differences in audience and format.

“Platforms come and go,” Yong said, but “really good storytellers can adapt to whatever is new.”

Perhaps the most vital information Yong conveyed was the effect storytelling has on the writer, specifically when it comes to investigating heavy scientific topics such as disease. Enduring gaslighting, scrutiny, and pain are all common in his field. The key to dealing with burnout, he explained, is as follows: doubling down on one’s duty and mission, finding strength within the community, and/or stepping away – either temporarily or permanently. It is up to the affected person to decide what choice is best for them.

As Yong expressed, you cannot take on the burden of others’ pain unless you lighten your own burden first. Take care of your mental – and physical – health before and after tackling heavy issues. You may not realize the toll telling a story takes until you find yourself burning out.

Despite its potential negative effects, Yong believes his field is extremely rewarding. He finds strength in scientific journalism and in bringing attention to topics people often disregard. As for his success and why he perseveres, he quotes Sean Thomas Dougherty:

“Why bother? Because right now, there is someone out there with a wound in the exact shape of your words.”

By Quinn Richards, Center for Communicating Science graduate assistant