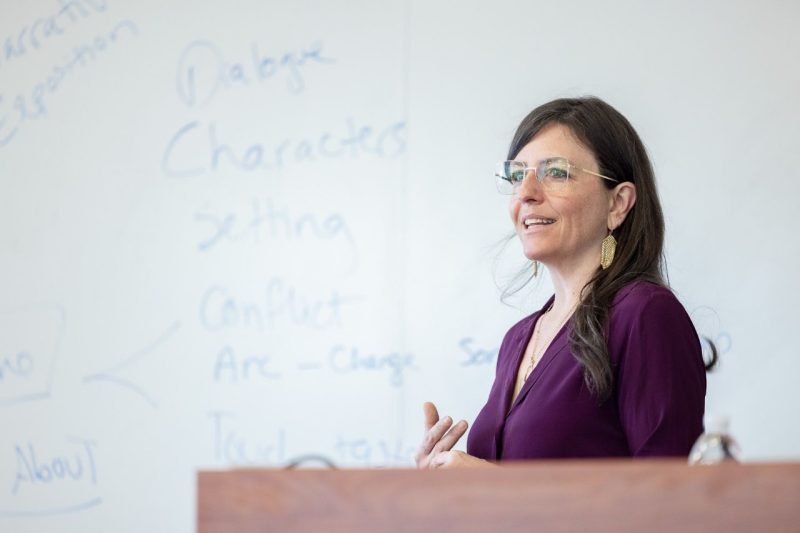

Author Rebecca Skloot Shares Science Writing Tips in Narrative Nonfiction Seminar

May 18, 2023

As a college student, Rebecca Skloot was a science major who took a creative writing course because her university accepted it as her foreign language requirement. A few decades later, the journalist and New York Times best-selling author is a science writer with a special interest in unintended consequences.

Skloot, author of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, is currently at work on a book about the use of animals in research. Joined by members of the Lacks family, she visited Virginia Tech on April 11 and delivered the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science’s 2023 Hugh and Ethel Kelly Lecture, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Earlier in the day, Skloot led a seminar in narrative nonfiction writing for Virginia Tech graduate students interested in science communication.

With a Master of Fine Arts in creative nonfiction, Skloot is familiar with misconceptions associated with word choice.

“Creative nonfiction doesn’t mean you can get creative with the facts,” she told her audience, many of whom were current or former Communicating Science (GRAD 5144) students. Instead, she said, creative nonfiction reads like fiction but is entirely fact-based.

“People should feel like they’re watching a movie or reading a novel, but by the end they’ve learned a bunch of science,” she said.

Skloot went over some of the elements of storytelling, including character, conflict, setting, dialogue, and narrative arc. She discussed the ways in which vivid dialogue and characters can really grab people, as can the use of sensory details in description. What she loves about science writing, she said, is the ready supply of conflict: “There are all sorts of hurdles and drama and conflict in research.”

Skloot feels that story arc and story structure are undertaught but essential topics.

“The way you put together all the pieces determines whether anyone will read your story,” she said. In what order will you tell the story? Which scenes are most compelling? What facts are important and which can be left out?

Introducing the concepts of narrative (story) and exposition (facts), Skloot used a piece of her own writing to demonstrate how to hook readers with a narrative, work in a section of exposition, return briefly to the narrative, add more exposition, and end with a final scene from the narrative. Her New York Times story on veterinary care for fish, “Fixing Nemo,” carries the reader through one specific goldfish surgery (an intended spaying that turns out to be a neutering) with interspersed information that readers may be curious about.

“You can go all over the place in your story as long as readers know you’re going to come back to the narrative,” she said. In the case of “Fixing Nemo,” the amount of space devoted to the goldfish surgery is actually quite small, she said. “What’s the story about? The story is about the evolution of a field of science.”

Most of the seminar participants were researchers, and Skloot encouraged them to think about the compelling stories they have to tell. She urged them to feed off of others’ interests, taking note of when people’s eyes light up — or when they glaze over — during conversations about research. Like lab researchers, she said, she gets “buried in her research” and loses perspective about which parts of it may be fascinating to others.

Although Skloot now has software and apps to help her organize her information, when she wrote The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, she used color-coded index cards to record facts, scenes, and other story elements.

“I spent a year arranging index cards on the wall,” she laughed. The book ended up being an intricate braid of three separate narratives, each starting at a different point in time but finally meeting.

One of the things that helps make her work successful, she says, is that she genuinely wants to hear people’s stories. The animal research book she’s currently working on has led her to lots of previously untold stories — and they are stories she wants to hear and convey to others.

“I’m not coming in with an agenda about what your story is,” she said. “I really want to hear your real story. And I don’t know what my story is going to be until I’ve done all the research.”

That research is what Skloot loves about her work. But in doing the research, she accumulates a huge amount of material.

“What no one ever told me about being a writer is that so much of the job is data management,” she said. She records every interview, takes thousands of photographs to help jog her memory when she is recreating scenes, and keeps notebooks while she is traveling and interviewing.

When asked how she knows when she is done with the research part of her projects, she quoted author John McPhee, who she once heard say that you know you’re finished when you find yourself “catching your own tail.”

“When I find myself telling my sources things they don’t know, because I now know the story in all its complexity, I know I’m catching my own tail,” she said.

The next step is writing, and Skloot said she uses the “vomit first, clean up later” writing method. The first draft of her Henrietta Lacks book was twice as long as the published version, she said.

Skloot is driven by genuine curiosity, by a fascination with unintended consequences, and by the cost of hiding things, she said. She suggests that we ask ourselves: “What is the cost of not communicating about something?”