“Courageously Correct and Retract”: Science's Holden Thorp on Building Trust Through Transparent Science Communication

June 24, 2025

Publishing a paper is one of the most significant things scientists can do during their careers. Each published paper represents years of carefully analyzing data, meticulously choosing the words on the page — dozens, sometimes hundreds of times — and passing a rigorous peer-review process. Yet, mistakes — both small and large — sometimes appear in published work.

At his visit to Virginia Tech on April 22 as part of the Research Integrity and Scholarly Excellence (RISE) lecture series hosted by Virginia Tech's Division of Scholarly Integrity and Research Compliance, Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of the Science family of journals, discussed the importance of acknowledging these mistakes. Errors can range from off-the-cuff comments — like excitedly, but accidentally, overstating results during a public interview — to mistakes that are so serious, they challenge the validity of an entire body of published work.

Thorp's full talk, "Maintaining and Communicating a Robust Scientific Record in an Age of AI and Social Media," can be watched through the RISE Lecture Series recordings archive page.

When an error is discovered, and submitting a correction is not sufficient, often the most responsible remedy to the situation is to retract the published paper. Unfortunately, this can be a very public process, leaving researchers feeling vulnerable to criticism and scrutiny from their peers and the public. These potential consequences may make it even harder for scientists to admit to being wrong.

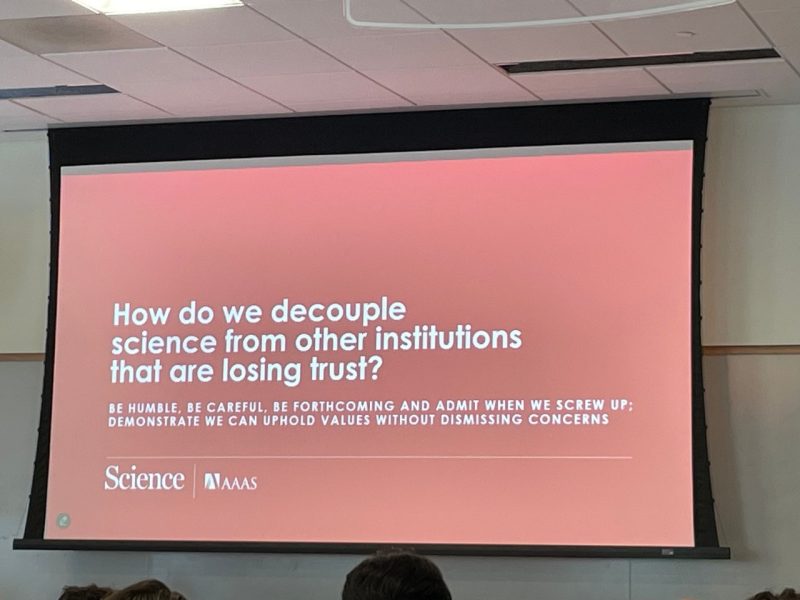

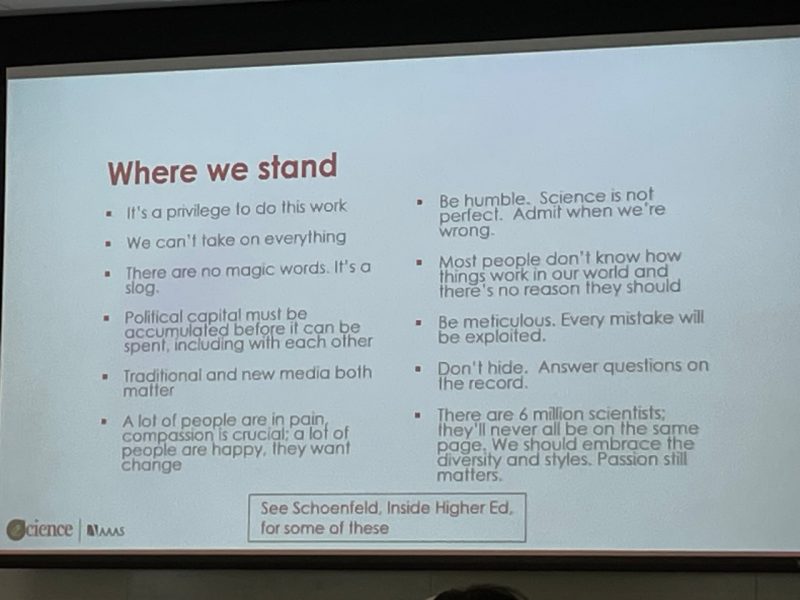

Nonetheless, Thorp urged scientists to “be humble, be careful, be forthcoming, and admit when we screw up.” He argued that scientists must “courageously correct and retract” and that the relationship between science and the public relies on such transparency.

“The public wants to know that we are willing to change our mind when we see data that's to the contrary of what we do,” Thorp said. More about Thorp’s thoughts about this topic can be found in his editorial published in Science magazine.

Thorp argued that the need to admit to mistakes should stem from a sense of obligation. Graduate students early in their scientific careers are among the most vulnerable in the scientific community and often rely on established methods to ask new research questions.

“If you’re a grad student who is reading this paper, should you go spend your time repeating [an] experiment or not?” Thorp asked. “Our moral obligation to that graduate student is more important than any other obligation in this picture…the graduate student who might go waste their time repeating an experiment [with an error] because we didn’t put a note [of concern] on it.”

Accountability also extends to the public. “We have the privilege of using taxpayer money to do research, and we have obligations to the people who paid [for] that,” said Thorp. Often, the public does not see the revision step of the scientific method — where scientists use feedback or new results to refine their hypotheses and experiments. Greater transparency about this crucial step can go a long way in helping the public understand how science works, Thorp said.

Thorp added that increased transparency about personal motivations can also help the public understand why mistakes happen in the first place. Like many, scientists sometimes struggle to admit when they’re wrong. “We’re human beings who have all the same human frailties as everybody else,” Thorp reminded the audience during the Q&A. He emphasized that “scientists are not just brains in a jar” operating completely devoid of emotion, a reference to a paper published in the Nature journal Climate Action by climate scientist Dr. Katherine Hayhoe and her team. Acknowledging this humanity makes it easier for scientists to admit when they’re wrong, while helping the public understand that they can trust science to “self-correct.”

And when mistakes inevitably happen, scientists can still control some of the narrative by providing transparency, Thorp suggested. “If you don’t give [the media] a comment, they think you’re hiding something," he said. "The sooner you correct or retract your paper if there's a problem, the less you lawyer up and deny things, the better the public perception of science.”

Of course, Thorp pointed out, scientists should strive to avoid mistakes in the first place by practicing careful scientific communication and ensuring that original data, results, and conclusions are reported faithfully in publications. “Every mistake will be exploited,” Thorp warned.

But when it comes to communicating to the public, Thorp concluded his talk by urging scientists to enlist the help of science communicators and to value their expertise. Science communicators serve as important liaisons between scientists and the public, he said, carefully translating scientific information and making it engaging and accessible to general audiences.

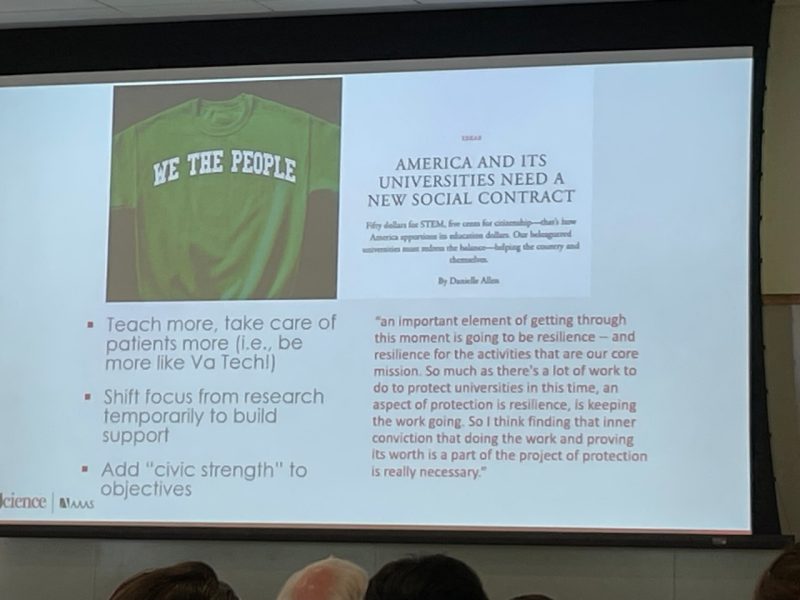

“The most important thing is for us to have respect and admiration for people who do these other things that we need,” Thorp said, referring to science communicators. Institutions too often prioritize research above all else, resulting in the work of classroom, science, and museum educators and science journalists being undervalued and underused, he said, adding, “There’s more to science than just doing stuff with the pipette in your hand.”

By Sara Teemer Richards, Center for Communicating Science editorial specialist